Fibromatosis of the breast: a case report and literature review

Highlight box

Key findings

• Breast augmentation surgery can predispose the development of secondary breast fibromatosis which poses unique challenges in diagnosis and treatment.

What is known and what is new?

• Breast fibromatosis is a rare, benign tumor that is difficult to diagnose and requires careful consideration of history, clinical, imaging, and pathologic findings.

• We report a case of a patient with secondary breast fibromatosis who underwent surgical management.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Further investigations in the pathophysiology and management of breast fibromatosis are critical to gain a better understanding of this rare, but important, condition.

• We advocate for individualized treatment strategies in the management of breast fibromatosis to optimize patient outcomes.

Introduction

Fibromatosis of the breast is a rare, locally aggressive benign tumor that mimics breast cancer on physical exam, mammography, and breast ultrasound and is best differentiated from malignancy histologically (1). The average age of presentation is between 25–45 years, with a mean age of 30 years. It is a rare but clinically relevant condition and poses unique challenges in both diagnosis and management. These challenges require a comprehensive exploration of the distinctive characteristics and implications of breast fibromatosis on patient care. Representing only 0.2% of all breast tumors, desmoid type fibromatosis’ (DTF) rise in prevalence has created new considerations in its management (2).

Historically, the term desmoid is derived from the Greek root terminology desmos, which was coined after German physiologist Johannes Mueller first described the tendon-like consistency of the tumor. This same tumor line was later confirmed by Nichols after encountering the same findings in abdominal tumors. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors are also known as deep fibromatosis (3). Desmoid tumors represent 3% of soft tissue tumors (4). These non-encapsulated tumors are predominantly found in the abdomen and thigh, and rarely seen in the breast. Desmoid tumors do not tend to metastasize; however, they are locally aggressive and infiltrative, and have a high recurrence rate (4). Resembling cancer on radiographic modalities, breast fibromatosis is definitively diagnosed by needle biopsy (5). They commonly occur in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and have been associated with pregnancy and previous surgical trauma (6). Estrogen has been hypothesized to have an influence on the development of fibromatosis of the breast due to the predominance of cases in women and the growth of these lesions during pregnancy (3).

A recent study has proposed categorizing breast fibromatosis cases into two distinct groups: primary and secondary (7). The primary category involves patients without prior exposure to surgery or radiation, while the secondary category includes those who develop fibromatosis following surgical interventions or radiation. Here we present a case of a patient with a remote history of breast augmentation who subsequently developed secondary fibromatosis. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-84/rc).

Case presentation

A 34-year-old female presented with a 6-month history of a 1-cm firm palpable right breast mass. She denied any associated pain, growth in size, or other skin changes. She has a family history of a maternal aunt with breast cancer diagnosed under the age of 50 years, a paternal grandmother with pancreatic cancer, and a paternal grandfather with prostate cancer. She has a surgical history of tonsillectomy as a child and bilateral breast augmentation 10 years prior with no complications. She has no pertinent past medical history and is otherwise healthy.

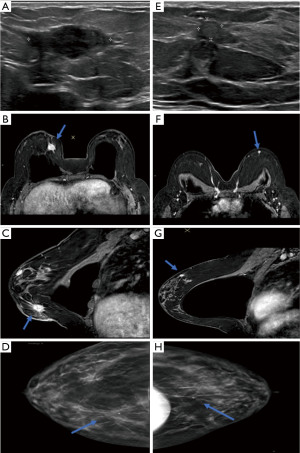

The patient underwent diagnostic bilateral mammography and ultrasound evaluation, which revealed a right breast mass in the right lower inner quadrant at 4 o’clock along the scar line measuring 1.9 cm × 1.7 cm × 0.8 cm with surrounding vascularity. The right breast mass was initially thought to represent fat necrosis and was categorized as Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) Assessment Category 3. A 6-month follow-up right breast ultrasound was subsequently performed, revealing a 1.7 cm × 2.7 cm × 1.0 cm irregularly shaped hypoechoic mass with angular margins in the lower inner quadrant of the right breast at 4 o’clock (Figure 1). She underwent ultrasound-guided right breast biopsy of the 4 o’clock mass, with pathology revealing fibromatosis [note was made that the lesion is positive for nuclear beta-catenin, smooth muscle actin, and CD10 and negative for AE1/AE3, high molecular weight (HMW) (34betaE12), desmin, S100, CD34, and bcl2].

The patient then underwent breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination, which revealed an enhancing right breast mass with central necrosis and an associated biopsy clip in the lower inner quadrant measuring approximately 2.5 cm × 1.7 cm × 1.3 cm (Figure 1). Note was made of a progressive pattern of enhancement supporting the known pathologic diagnosis of fibromatosis. The MRI also identified multiple areas of progressive enhancement in the left breast which were consistent with findings in the right breast. The most prominent of these was a 1.0-cm irregularly shaped enhancing mass in the upper region of the left breast. MRI-guided left breast biopsy revealed breast tissue with bland spindle cell proliferation and note was made that the combined morphologic and immunohistochemical findings may be compatible with fibromatosis (keloidal pattern) in the appropriate clinical setting. No diagnostic challenges, such as access to testing, financial, or cultural were reported by the patient.

The patient was taken to the operating room for outpatient bilateral localized excisional biopsies. The surgical pathology on the right revealed breast fibromatosis noted in the background of benign breast tissue. The surgical pathology on the left revealed focal fibromatosis noted in the background of benign breast tissue with fibrocystic changes. The histological examination revealed elongated intersecting fascicles characterized by bland spindle cells exhibiting indistinct cellular borders (Figure 2). These cells manifested hyperchromatic nuclei, sporadic nucleoli, and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Infiltration was observed within the normal architecture of ducts, lobules, and adipose tissue, devoid of mitotic activity. The background stroma displayed collagen thickening akin to keloid formation. No dysplasia or hyperplasia was noted in either breast. The patient had an uncomplicated post-operative course.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Fibromatosis of the breast has a vague clinical presentation and warrants thorough radiological investigation due to its cancer-like appearance. Common radiographic modalities, such as ultrasound, mammogram, computed tomography (CT) scan, and MRI, have each proven unique advantages and challenges in evaluating breast fibromatosis. On mammography, nearly 80% of breast fibromatosis receive a BIRADS category of 4 or 5, with a recommendation for biopsy (8). Notably, CT scans have shown optimal visualization of these masses that are at least 5 cm in size (9). Radiographic studies have highlighted features in breast fibromatosis that are similar to breast cancer, such as unclear borders (72.4%), irregular shape (75.9%), and rough edges (69%) (8,10). Interestingly, breast fibromatosis typically lacks calcifications or vascularity on doppler ultrasound. MRI is recommended when muscle involvement is suspected to assess the extent of invasion (10). Additionally, MRI plays a crucial role in post-treatment follow-up and monitoring for tumor recurrence.

Breast fibromatosis requires a core-needle biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Expert histopathological analysis by a pathologist specializing in mesenchymal tumors is essential (11). Findings typically reveal long fascicles of bland spindle cells, predominantly fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, with abnormal beta-catenin nuclear positivity and negative CD34 staining (10). At the cellular level, the upregulation of beta-catenin by the WNT pathway correlates with fibromatosis. Activation of this pathway promotes cell proliferation by preventing antigen presenting cells (APCs) from phosphorylating beta-catenin, allowing its translocation into the nucleus for proto-oncogene transcription (11). This signaling pathway has been shown to have an important role in wound healing as elevated beta-catenin levels have been noted in the hyperplastic stage of wound healing and its dysplastic activity has been shown to be pathogenic in the development of hyperplastic scars (6). Research indicates dysregulation of beta-catenin accumulation in 70% of desmoid tumors, stimulating oncogenes, and collagen proliferation influenced by estrogen stimulation (4). Estrogen receptor beta signaling (ErB) and cyclin D1 significantly contribute to tumor cell proliferation, with elevated Erb expression potentially predicting postoperative recurrence (12). In cases of uncertainty with pure histological diagnosis, genetic analyses can be considered to confirm suspicions (2,11).

Dysplastic wound healing from previous surgical trauma plays a role in the pathogenesis of breast fibromatosis. A trend seen not only in our case, but also in a number of previous publications, breast augmentation has been described as a risk-factor for the development of breast fibromatosis (3,6,9). Augmentation with silicone and saline implants have been implicated and fibromatosis is suspected to arise from the fibrous capsule that develops around the implants (2,4). Breast desmoid tumors have been found to be associated with implant-based breast reconstruction in 10% of cases and tend to occur within 3 years after placement (6). Most cases involve silicone implants versus saline implants, but this may be related to the higher frequency of silicone implant use (3).

The recommended management of fibromatosis is wide local excision with negative margins. Margins >1 cm have been found to be associated with fewer incidents of recurrence (7). In a retrospective study performed by Neuman et al., a 29% recurrence rate was identified at a median of 15 months. They found lower age to be a significant risk factor for recurrence with a median age of 28 in those experiencing recurrence versus 46 years in those that did not recur. A trend was also noted towards more frequent recurrences in patients with positive margins versus negative margins, in addition to patients with larger tumors (13).

Considering the implication of hormonal signaling in this disease process, integrating systemic therapy has been described. The exact mechanism of action of hormonal agents on fibromatosis is unknown but is thought to be from the modulation of the estrogen-receptor. It has also been proposed to be from the deprivation of a growth signal or cytokine in the Wnt/beta-catenin tumor suppressor pathway (5,14). Since most breast fibromatoses lack estrogen or progesterone receptors, clinical benefit from tamoxifen would be through mediation of the Wnt/beta catenin tumor suppressor pathway (5,14). The data for systemic therapy for fibromatosis are limited and derived from small series and case reports and mostly in extramammary fibromatosis cases. It can be classified into a cytotoxic or non-cytotoxic approach. Non-cytotoxic approaches include antiestrogens such as tamoxifen that can be used alone or in combination with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as sulindac (5). Imatinib, a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, has also been used in patients with desmoid tumors. In a prospective study, patients with unresectable and progressive symptomatic fibromatosis with intra and extra-abdominal primary sites were treated with imatinib (400 mg/day) for 1 year and found to have a 2-year progression-free and overall survival rate of 55% and 95%, respectively (15). The use of tamoxifen in fibromatosis has shown a regression rate of 15–20% and has shown symptomatic improvement with stabilization of disease in 25–30% of patients which results in a clinical benefit range of up to 50% (16). The use of tamoxifen (10 mg twice daily) in a 29-year-old female with breast fibromatosis resulted in a considerable decrease in the size of the mass from 10.5 to 5.9 cm at 14 months (5). Cytotoxic approaches are considered last resort and are most commonly doxorubicin-based combinations (5). Other regimens, mostly for intraabdominal desmoids, that have been described include anthracycline monotherapy, methotrexate, and vinca alkaloids (5). Overall, the use of systemic therapy in the management of breast fibromatosis has limited evidence.

The use of radiation therapy for desmoid tumors has been discussed in the literature. For extramammary desmoid tumors, local control rates of 73–94% have been described (5). Control rates with radiation and surgery have trended to be better than with surgery alone in desmoid tumors outside of the breast. However, the use of postoperative radiation in breast fibromatosis has not been well established or accepted.

Modern medicine recognizes the efficacy of an individualized approach. Active surveillance (AS) is also accepted as an initial strategy, with regular clinical follow-ups every 3 to 6 months and ultrasound imaging; especially when stability or spontaneous regression is observed (11,17). The AS approach was found to be effective in the case of bilateral breast fibromatosis (11). At 3-year follow-up, they noted continuous regression of the breast fibromatosis that reached 73% and 21% in the left and right breast, respectively (11). Surgical intervention becomes necessary in cases of aggressive growth to prevent muscle involvement or chest cavity complications (10,17).

This case report highlights the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of breast fibromatosis in a patient with prior breast augmentation surgery. Strengths associated with this case report include a comprehensive diagnostic approach using multiple imaging modalities and histopathological analysis, along with insights into the pathogenesis involving tissue injury and surgical trauma. However, some limitations include the single-case nature of this study and the lack of long-term follow-up. Despite these limitations, this report emphasizes the importance of individualized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for effective management of fibromatosis.

Conclusions

This case highlights the association between previous surgical trauma, such as breast augmentation, and the development of secondary breast fibromatosis. While a conservative approach is plausible for patients displaying fibromatosis, we advocate for a personalized treatment strategy. Post-operative surveillance is essential for patients with breast fibromatosis due to its local aggressiveness and risk of recurrence.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-84/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-84/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-84/coif). E.O. received research funding from the Bristol Myers Squibb foundation for unrelated research work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Grimaldi MC, Trentin C, Lo Gullo R, et al. Fibromatosis of the breast mimicking cancer: A case report. Radiol Case Rep 2018;13:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelwahab K, Hamdy O, Zaky M, et al. Breast fibromatosis, an unusual breast disease. J Surg Case Rep 2017;2017:rjx248. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hill E, Merrill A, Korourian S, et al. Silicone breast implant associated fibromatosis. J Surg Case Rep 2018;2018:rjy249. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor TV, Sosa J. Bilateral breast fibromatosis: case report and review of the literature. J Surg Educ 2011;68:320-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Plaza MJ, Yepes M. Breast fibromatosis response to tamoxifen: dynamic MRI findings and review of the current treatment options. J Radiol Case Rep 2012;6:16-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kilmartin C, Westover C, Raghavan S, et al. Desmoid Tumor and Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction. Case Rep Oncol 2023;16:74-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghanta S, Allen A, Vinyard AH, et al. Breast fibromatosis: Making the case for primary vs secondary subtypes. Breast J 2020;26:697-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su HZ, Huang M, Li ZY, et al. Ultrasound characteristics of breast fibromatosis mimicking carcinoma. J Clin Ultrasound 2024;52:144-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiller VL, Arndt RD, Brenner RJ. Aggressive fibromatosis of the chest associated with a silicone breast implant. Chest 1995;108:1466-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winkler N, Peterson M, Factor R. Breast Fibromatosis: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. J Breast Imaging 2021;3:597-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hennuy C, Defrère P, Maweja S, et al. Bilateral breast desmoid-type fibromatosis, case report and literature review. Gland Surg 2022;11:1832-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santti K, Ihalainen H, Rönty M, et al. Estrogen receptor beta expression correlates with proliferation in desmoid tumors. J Surg Oncol 2019;119:873-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neuman HB, Brogi E, Ebrahim A, et al. Desmoid tumors (fibromatoses) of the breast: a 25-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:274-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarz GS, Drotman M, Rosenblatt R, et al. Fibromatosis of the breast: case report and current concepts in the management of an uncommon lesion. Breast J 2006;12:66-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Penel N, Le Cesne A, Bui BN, et al. Imatinib for progressive and recurrent aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors): an FNCLCC/French Sarcoma Group phase II trial with a long-term follow-up. Ann Oncol 2011;22:452-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel SR, Benjamin RS. Desmoid tumors respond to chemotherapy: defying the dogma in oncology. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:11-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Draper AJ, Shapiro AJ. When to Cut: A Case of Breast Fibromatosis. Am Surg 2023;89:2883-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Sogunro O, Joseph-Pauline S, Oluyemi E, Lee S, Pinco J. Fibromatosis of the breast: a case report and literature review. AME Case Rep 2025;9:24.