Analysis of misdiagnosis and mistreatment of 11 cases of non-tuberculous testicular abscess: case series

Highlight box

Key findings

• Clinical manifestations of testicular abscess can be diverse and atypical, making it easy to misdiagnose and mistreat, which in turn leads to unnecessary orchiectomy.

What is known and what is new?

• Testicular abscesses often present as “redness, swelling and pain” in the scrotum and are often treated with antibiotics.

• However, imaging of testicular abscess is sometimes difficult to distinguish from testicular tumor and testicular torsion, and in patients with extensive abscess formation and severe swelling, conservative treatment is not indicated in all cases.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Diagnosis and treatment should be combined with comprehensive analysis of the medical history and accurate differential diagnosis.

Introduction

A non-tuberculous testicular abscess is primarily a consequence of late-stage urinary tract inflammation. As the disease progresses, the clinical symptoms may not always be characteristic enough, and imaging manifestations can be challenging to differentiate from testicular tumors and testicular torsion. As the condition worsens, the spermatic cord’s blood flow is compromised, which can result in tissue injury, testicular ischemia, hypoxia, testicular infarction, or even distant testicular atrophy. In this sense, the prognosis of patients with nontuberculous testicular abscesses will be greatly influenced by the timely and accurate diagnosis, as well as the fact that standard antibiotic therapy alone is frequently insufficient in this respect. We retrospectively analyze the data of 11 cases of non-tuberculous testicular abscesses that underwent surgical treatment and were confirmed to be non-tuberculous testicular abscesses by pathological examination, as well as review and report the literature, in the hope that it will be useful to medical colleagues in the diagnosis, differentiation, treatment plan, and timing of surgery for non-tuberculous testicular abscesses in future clinical work. We present this case series in accordance with the AME Case Series reporting checklist (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-222/rc).

Case presentation

From 2006 to 2023, clinical data were collected from 11 patients who were identified with non-tuberculous testicular abscesses by pathologic examination following surgical therapy in our hospital’s Department of Urology. The age range of the first visit was 18 to 78 years old (the median age was 48 years old); all of them presented to the doctor with the first complaint of an enlarged scrotum with pain on the affected side; two patients had no fever during the course of the disease; the highest temperature of the febrile patients was 40 ℃; the shortest history of the disease was 2 days; and the longest was no more than 2 months. Only one patient complained of a history of urinary tract infection prior to admission, one had a recent history of ipsilateral scrotal trauma, and one had a recent history of ipsilateral testicular sheath reversal; the case characteristics of the 11 patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Number | Age (years) | Antecedent history | Combined epididymitis | Preoperative diagnosis | Image | Laboratory result | Duration of symptoms/hospitalization (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | ‘Testicular surgery’ in early childhood | No | (I) Right testicular tumor | Scrotal ultrasound: a medium-low solid mass measuring approximately 2.4 cm × 1.9 cm was detected in the upper level of the right testis, accompanied by internal echoes of uneven strength and abundant blood flow. Enhanced CT: inhomogeneous enhancement of the right testis | Blood routine examination (−), urine routine test (−), tumor markers (−), urine culture (−) | 15/10 |

| (II) Prostatitis | |||||||

| 2 | 28 | No | No | Testicular pain on the right side (investigation of causes) | Scrotal ultrasound: right testicular injury sonogram with decreased blood flow, size approximately 3.4 cm × 2.4 cm; enhanced CT: inhomogeneous density enhancement of the right testis | Blood routine examination: white blood cell count: 22.05×109/L; neutrophilic granulocyte percent: 88%; C-reactive protein: 35.11 mg/L; procalcitonin: 0.49 ng/L. Urine routine test: white blood cell count 49/μL bacterial culture of pyogenic fluids: Escherichia coli | 2/3 |

| 3 | 55 | Gout | No | Necrosis of the left testicle | Scrotal ultrasound: diffuse enlargement of the left testicle, measuring approximately 4.1 cm × 3.0 cm, with uneven internal echogenicity and no significant blood flow signal | Blood routine examination (−), urine routine test (−), tumor markers (−), urine culture (−) | 30/6 |

| 4 | 47 | No | Yes | (I) Torsion of the right testicle? | Scrotal ultrasound: right testis enlarged, about 4.2 cm × 2.9 cm, no obvious blood flow signal in the parenchyma, epididymis enlarged, blood flow in the scrotal segment of the spermatic cord obviously reduced | Blood routine examination: white blood cell count: 16.40×109/L; neutrophilic granulocyte percent: 88.2%; urine: urine routine test (−); bacterial culture of pyogenic fluids: Escherichia coli | 15/6 |

| (II) Bilateral testicular syringomyelia | |||||||

| 5 | 51 | Recent history of lower urinary tract infection | Yes | (I) Left testicular occupancy (nature to be investigated) | Scrotal ultrasound: right testis dysmorphic, size about 2.9 cm × 2.6 cm, parenchyma without obvious blood flow signal, enlarged epididymis | Blood routine examination: white blood cell count: 11.40×109/L; neutrophilic granulocyte Percent: 76.7%. Urine routine test: white blood cell count 15/μL; urine culture (−); bacterial culture of pyogenic fluids: Escherichia coli | 30/15 |

| (II) Gallbladder stones | |||||||

| 6 | 33 | No | Yes | (I) Left testicular occupancy (nature to be investigated) | Scrotal ultrasound: dysmorphic left testis measuring approximately 5.4 cm × 3.7 cm with disturbed blood flow signal and enlarged epididymis; enhanced CT: cystic solid mixed density shadow with uneven enhancement in the left testicle | Blood routine examination: white blood cell count: 11.11×109/L. Urine routine test: white blood cell count 27/μL | 60/15 |

| (II) Gallbladder stones | |||||||

| 7 | 72 | History of surgery for left testicular syringomyelia, hypertension | Yes | (I) Left epididymis and testicular hematoma with infection | Scrotal ultrasound: left testicle is markedly enlarged, with significant inflammatory edema detected in the peritesticular tissue, measuring approximately 6.2 cm × 4.7 cm. CT plain scan: left testis increased in size, with a large amount of fluid and free stagnant gas seen in it | Neutrophilic granulocyte percent: 81.8%; urine routine test (−) | 20/7 |

| (II) Left testicular syringomyelia after surgery | |||||||

| (III) Hypertension | |||||||

| 8 | 50 | History of closed trauma to the right testicle | Yes | Right testicular abscess? | Scrotal ultrasound: the right testicle was dysmorphic, measuring about 4.3 cm × 2.9 cm, and a mixed cystic hypoechoic mass of 4.4 cm × 3.4 cm was detected in the scrotum | Blood routine examination: white blood cell count: 10.73×109/L; urine routine test (−); bacterial culture of pyogenic fluids: Escherichia coli | 30/20 |

| 9 | 62 | Hypertensive | No | (I) Left testicular occupancy | Scrotal ultrasound: diffuse enlargement of the left testis with irregular hypoechoic areas with abundant blood flow signal; enhanced CT suggests that the left testis is enlarged in size, about 5.1 cm × 3.5 cm, and has cystic-solid mixed density shadow changes, accompanied by some obvious enhancement | Neutrophilic granulocyte percent: 75.6%; urine routine test: white blood cell count: 37.4/μL; urine culture: Escherichia coli | 30/10 |

| (II) Prostatic hyperplasia | |||||||

| (III) Hypertension | |||||||

| 10 | 52 | Previous hypospadias repair | No | Torsional necrosis of the right testicle? | Scrotal ultrasound: right testis is dysmorphic, measuring approximately 3.1 cm × 1.9 cm, with no significant blood flow signal in the testicular parenchyma | Blood routine examination: white blood cell count: 22.98×109/L; neutrophilic granulocyte percent: 92.5%. Urine routine test: white blood cell count 5.4/μL; bacterial culture of pyogenic fluids: Escherichia coli | 30/8 |

| 11 | 78 | No | Yes | Possible right testicular abscess? | Scrotal ultrasound: right testis is dysmorphic, measuring approximately 3.1 cm × 1.9 cm, with no significant blood flow signal in the testicular parenchyma | Blood routine examination (−), urine routine test (−), urine culture (−) | 60/13 |

CT, computed tomography.

Scrotal redness, swelling, and hot pain were observed in 56% of cases in this group; abnormalities were found in 45% of urine routines; abnormalities in blood routines were found in 73% of cases; and abnormalities in urine cultures were found in 25% of urine culture cases; All patients received antibiotic treatment; there was no incidence of postoperative incision infection or delayed healing in the group of 11 patients, nine of whom underwent orchiectomy of the afflicted side and two of whom underwent scrotal incision and drainage alone. There was no history of diabetes in any of the 11 patients. All procedures performed in this case series were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Tuberculous epididymal and testicular abscesses are relatively common in the clinic, while non-tuberculous testicular abscess is a rare infectious disease in urology that is reported to be mostly seen in infants and adolescents (1), and testicular abscess is mostly unilateral in onset and bilaterally rarer. It is often secondary to inflammation of the genitourinary system, mostly occurring in patients with urethritis, cystitis, prostatitis, and long-term indwelling catheters (2). Studies have revealed that 5.5% of untreated or advanced epididymo-orchitis cases can result in the formation of an abscess (3). The infection can reach the epididymis and testis through the lymphatic system, blood circulation, or retrograde pathway. Patients may also experience ischemia necrosis of the testis as a result of twisting of the testicular spermatic cord; in a small percentage of cases, an inguinal incarcerated hernia may potentially be the underlying cause (4).

In half of our cases, epididymitis was thought to be a secondary complication of testicular epididymitis; their scrotal ultrasound revealed images suggestive of epididymitis; and two out of eleven patients had a history of ipsilateral scrotal trauma and surgery, which we thought might have been caused by a combination of bacterial infection and testicular injury. According to earlier research, the causative organisms of testicular abscesses are similar to those of epididymal orchitis in that they typically cause infections in men in two age groups: men between the ages of 14 and 35 years are typically infected by sexually transmitted Neisseria gonorrhea or Chlamydia trachomatis, while men over the age of 35 years are typically infected by Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus (5,6). Here, we reiterate the importance of thoroughly considering and ruling out testicular abscess caused by Mycobacterium TB in patients with a suggested diagnosis of nontuberculous testicular abscess. An enlarged and painful scrotum is a common clinical manifestation of non-tuberculous testicular abscesses, which is frequently accompanied by fever, nausea, vomiting, and other symptoms. However, temperature changes should not be used to gauge the severity of the condition, as in this group of patients, some may present with a high fever up to 40 ℃, while others may have a low fever or none at all (7).

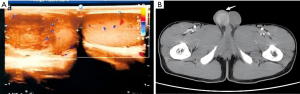

The differential diagnosis of a non-tuberculous testicular abscess is also critical and should be differentiated from testicular torsion and testicular tumors. In the early stage, due to the limitations of the abscess, the clinical and imaging manifestations were often atypical, which often led to misdiagnosis; Atypical clinical indications and signs of probable malignancies on computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and other imaging led to radical orchiectomy in two of the eleven patients (Figure 1A,1B), but their postoperative histological examination revealed purulent inflammation along with the formation of an abscess (Figure 2), and the postoperative histopathological examination showed suppurative inflammation with abscess formation, and it is interesting that one patient was negative for laboratory infection markers. In addition, five of the eleven patients had a scrotal ultrasound appearance of the testicular blood flow signal on the affected side decreasing or disappearing (Figure 3A), which makes it difficult to exclude testicular torsion; however, no spermatic cord torsion was found during the operation.

One patient had sudden unilateral scrotal swelling and pain. His medical history was only 2 days old, and his past history was unremarkable. The highest body temperature was only 37.8 ℃ during the course of the disease. Ultrasound showed that the testicular blood supply of the affected side was decreased (Figure 3A). Enhanced CT is also consistent with testicular torsion (Figure 3B). We highly suspected testicular torsion before surgery; however, no torsion of the spermatic cord or black necrosis of the testicular parenchyma were found during the operation. Then a testicular resection was performed with the consent of his family and postoperative pathology confirmed a testicular abscess. Prior research has indicated that constriction of the testicular and epididymal vasculature effectively causes a compartment syndrome, even if the precise mechanism by which testicular abscesses develop infarction is uncertain (8,9). Additional luminal compression may be caused by tissue edema, exudates, and acute inflammatory alterations. Concurrently, endothelial failure and venous congestion with the accompanying thrombosis raise pressure, causing hypoxia; circulatory deprivation may be influenced by elevated compartment pressures (10). Early surgical intervention and incision decompression are essential components of therapeutic care for these patients. Without a doubt, early diagnosis is the foundation of surgical intervention.

The same is true for other infectious diseases: routine urine and hematological tests are crucial. It is crucial to remember that not all hematological and urinalysis tests for testicular abscess are positive; in fact, some tests may come back negative. As such, the findings of these tests cannot be depended upon in a clinical environment to make a diagnostic diagnosis or gauge the severity of the disease. Imaging mostly relies on scrotal ultrasonography; however, distinguishing between tumors, abscesses, infarcts, and localized inflammatory alterations may be difficult when scrotal ultrasonography is conducted during the acute period (11). By now, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can bring more clarity to imaging manifestations that are unclear in conventional ultrasound and give a more accurate representation of tissue perfusion than conventional ultrasonography. CEUS has an important role in diagnosing testicular infarction, evaluating post-traumatic testicular parenchymal changes, and identifying tumors (12). In addition, it should be noted that intratesticular hematoma, testicular tuberculosis, focal infection, and segmental testicular infarction can also present as tumor-like on ultrasonography (Figure 1A) (13), when additional CT enhancement scans, MRIs, and serological tumor markers are required for further differential diagnosis. If CEUS is not possible and clinical suspicion of ischemia remains high, emergency MRI may be considered, with up to 100% accuracy in detecting testicular necrosis on T2-weighted images (14). In addition, for ambiguous clinical and imaging presentations, localized pathologic puncture may be a good adjunct to the diagnosis.

The early stage of testicular abscess is sensitive to antibiotic treatment; however, for patients with large abscess formation and severe swelling, conservative treatment may cause the disease to progress and lead to orchiectomy (7). Source control of testicular abscesses can be via complete or partial orchiectomy, open incision and drainage, as in our patient’s case, or percutaneous aspiration and drain placement. Ideally, the testes should be preserved if possible (15). But in fact, when we do scrotal exploration, we find that the testicular parenchyma is often black, necrotic, and without blood supply. It has been reported that the incidence of final orchiectomy during scrotal exploration is as high as 50% (3). In this group of cases, two patients only underwent scrotal incision and drainage, but unfortunately there was no follow-up data after discharge; the recovery of testicular function in the later stage is unknown. In addition, some researchers used testicular abscess incision and open drainage, followed by a secondary suture to close the wound, so as to preserve the affected testicle (15). However, whether the testicular atrophy occurred in the later stage of this case has not been reported. Besides, this method is also only applicable to the early testicular infarction that has not occurred, and the testicular parenchyma of the surgical side has been damaged to varying degrees. Inflammation may lead to an abnormal increase of tumor necrosis factor α and activate mitogen-activated protein kinase, the abnormal expression of blood-testosterone barrier structural proteins, and impaired integrity (16). Therefore, the long-term effect of this treatment also needs to be explored.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the clinical manifestations of testicular abscesses can be diverse and atypical; imaging or hematologic diagnosis alone is not enough but should be combined with a history of comprehensive analysis, accurate differential diagnosis, early and adequate use of antibiotics to prevent infection, and to be alert for testicular abscess formation. For confirmed patients, early operation should be considered to lift the obstruction of the spermatic cord and abscess drainage, to avoid further aggravation of inflammation and influence of testicular blood supply, and to reduce the risk of testicular atrophy and testicular resection.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the AME Case Series reporting checklist. Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-222/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-222/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-222/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this case series were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Yan L, Zhang Y, Lu Z. Testicular abscess secondary to spinal cord abscess: a case report. Clinical Journal of Medical Officer 2018;46:380-1.

- Wang Y, Sun X, Li Z. Neonatal testicular abscess: a case report. Journal of Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences 2006;27:19.

- Desai KM, Gingell JC, Haworth JM. Localised intratesticular abscess complicating epididymo-orchitis: the use of scrotal ultrasonography in diagnosis and management. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:1361-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu X, Ma G, Guo Y. Eight cases of neonatal scrotal abscess. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Surgery 2014;13:458-9.

- Trojian TH, Lishnak TS, Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:583-7. [PubMed]

- Azmat CE, Vaitla P. Orchitis. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing, 2020.

- Banyra O, Shulyak A. Acute epididymo-orchitis: staging and treatment. Cent European J Urol 2012;65:139-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alharbi B, Rajih E, Adeoye A, et al. Testicular ischemia secondary to epididymo-orchitis: A case report. Urol Case Rep 2019;27:100893. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandhi J, Dagur G, Sheynkin YR, et al. Testicular compartment syndrome: an overview of pathophysiology, etiology, evaluation, and management. Transl Androl Urol 2016;5:927-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hackett B, Sletten Z, Bridwell RE. Testicular Abscess and Ischemia Secondary to Epididymo-orchitis. Cureus 2020;12:e8991. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kühn AL, Scortegagna E, Nowitzki KM, et al. Ultrasonography of the scrotum in adults. Ultrasonography 2016;35:180-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sidhu PS, Cantisani V, Dietrich CF, et al. The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations for the Clinical Practice of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in Non-Hepatic Applications: Update 2017 (Short Version). Ultraschall Med 2018;39:154-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sweet DE, Feldman MK, Remer EM. Imaging of the acute scrotum: keys to a rapid diagnosis of acute scrotal disorders. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2020;45:2063-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parenti GC, Feletti F, Carnevale A, et al. Imaging of the scrotum: beyond sonography. Insights Imaging 2018;9:137-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lurz K, Santarelli S, Hager S, et al. Pediatric intratesticular abscess managed with a testicular sparing approach: A case report. Urol Case Rep 2021;40:101873. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Liu Y, Chen Y, et al. Influencing factors and related mechanism of blood-testis barrier injury. Chinese Journal of Reproduction and Contraception 2021;41:937-42.

Cite this article as: Li Y, Zhang Z, Zhao L. Analysis of misdiagnosis and mistreatment of 11 cases of non-tuberculous testicular abscess: case series. AME Case Rep 2025;9:38.