Life-threatening interstitial lung disease with adjuvant osimertinib after complete resection of non-small cell lung cancer: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• Severe adverse event is a very unfortunate and intolerable turn of events, particularly in the context of postoperative adjuvant therapy. This is a case report of a s life-threatening, severe drug-induced interstitial lung disease (ILD) that occurred during postoperative adjuvant therapy with osimertinib.

What is known and what is new?

• Osimertinib has been approved as a standard adjuvant treatment option following complete resection of lung cancer. The safety profile of osimertinib is generally favorable. However, osimertinib-induced ILD occurs as a critical and potentially fatal adverse event, especially in Japan.

• This case report presents a rare instance of ILD induced by osimertinib during postoperative adjuvant therapy following lung cancer resection. To date, only one other case of osimertinib-induced ILD during adjuvant therapy has been reported.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• As osimertinib is increasingly used in routine clinical practice as adjuvant therapy, similar cases of drug-induced ILD are expected to be encountered more frequently in the future. This case revealed the potentially fatal adverse effect of osimertinib and the difficulties of ILD in postoperative adjuvant treatment. Sufficient informed consent and patient selection is required when administering adjuvant osimertinib with potentially serious side effects.

Introduction

Background

Patients with stage IB to IIIA epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have demonstrated significantly longer disease-free survival among those who received osimertinib as adjuvant therapy after surgical resection (1) [ADAURA (AZD9291 Versus Placebo in Patients With Stage IB-IIIA Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma, Following Complete Tumour Resection With or Without Adjuvant Chemotherapy) ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02511106]. Osimertinib has since been approved as a standard adjuvant treatment option following complete resection of lung cancer.

Rationale and knowledge gap

The safety profile of osimertinib is generally favorable (2). However, osimertinib-induced interstitial lung disease (ILD) occurs as a critical and potentially fatal adverse event, especially in Japan (3). No reports described severe drug ILD in the ADAURA clinical trials. A report by Mitsuya et al. describes the only other known case of severe osimertinib-induced ILD following adjuvant therapy. The main concern is that such severe cases may become more common as osimertinib is increasingly used in postoperative therapy. Given the risk of severe ILD, thorough informed consent is especially important in the postoperative setting, where patient expectations of recovery are higher (4).

Objective

Here, we report a life-threatening severe drug-induced interstitial pneumonia that developed during osimertinib administration as adjuvant therapy following radical resection of lung cancer in a woman with no underlying disease and no smoking history. The patient survived with intubated ventilatory management and steroid therapy, but she required home oxygen therapy (HOT). This case revealed the potentially fatal adverse effect of osimertinib and the difficulties of postoperative adjuvant treatment. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-203/rc).

Case presentation

A 68-year-old female patient underwent resection of the lower lobe of her left lung to treat NSCLC. Surgery time was 82 min, and the patient was discharged from the hospital with no complications. Pathologically, she was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma with intrapulmonary metastasis p-T3N0M0 stage IIB and was positive for EGFR gene mutational status (Ex L858R). She reported no history of smoking. She exhibited no underlying disease and no history of interstitial pneumonia.

She received standard postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy [3 cycles of cisplatin (60 mg/m2, on day 1) and vinorelbine (25 mg/m2, on day 1 and 8)] given intravenously every 3 weeks, starting 36 days postoperatively. Adverse event of grade 2 decreased appetite was detected during chemotherapy, following the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade version 5.0 (5). Oral osimertinib at 80 mg once daily was initiated as adjuvant chemotherapy 112 days postoperatively.

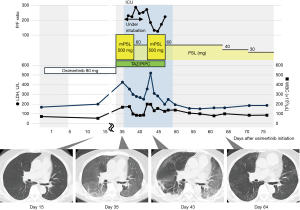

The patient remained hospitalized until day 7, during which close monitoring was performed, including blood tests and imaging studies. On day 15, follow-up blood tests, computed tomography (CT) imaging, and clinical examinations were conducted on an outpatient basis, which revealed no significant abnormalities (Figure 1). However, the patient presented to the hospital at 35 days, with severe fatigue, loss of appetite, and respiratory distress that appeared 2 days before hospital admission. At presentation, the patient exhibited severe symptoms, including marked fatigue, loss of appetite, and respiratory distress. She was barely able to walk a few meters unassisted and required the support of family members to reach the hospital. Upon hospital arrival, the oxygenation level decreased to saturation of percutaneous oxygen (SpO2) of 78% on room air and 92% on nasal cannula 3 L/min oxygenation.

Chest CT demonstrated widespread ground-glass opacifications throughout all lung fields. She was admitted to the hospital on the same day. Osimertinib was discontinued, and antibiotics, tazobactam and piperacillin, and methylprednisolone (500 mg/day) were initiated. However, oxygenation worsened rapidly during the night on the same day of admission, and SpO2 could only be maintained at 89% under an oxygenation concentration of 65% and flow of 40 L even with a high-volume nasal cannula device. The next day (36 days after osimertinib administration), she was intubated and placed on ventilatory management. The patient was diagnosed with osimertinib-induced grade IV ILD with severe hypoxemia.

The partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio tended to improve after 5 days of methylprednisolone (500 mg/day) and subsequent prednisolone of 60 mg/day; hence, the patient was extubated on 41 days and ventilatory management was completed.

In this case, treatment began with 500 mg of methylprednisolone administered daily for 5 days, followed by maintenance therapy with prednisolone at 1 mg/kg, tapered weekly in 10 mg increments. Tapering was guided by subjective symptoms, oxygenation levels, laboratory findings such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and white blood cell (WBC), as well as the absence of worsening CT abnormalities. However, on day 43, 2 days after extubating, oxygenation decreased, ILD markers, such LDH and WBC worsened, and consolidation exacerbated and reticular shadows appeared in some parts of ground-glass opacities on CT. Methylprednisolone (500 mg/day) was again administered for 5 days, and she was started on prednisolone of 60 mg/day, and respiratory status and ILD markers gradually improved during the taper, thereafter.

The consolidation and diffuse ground-glass opacities on CT almost disappeared on day 64. The patient was discharged from the hospital on day 72 with a maintenance dose of 30 mg/day of prednisolone. By the time of discharge, her severe fatigue had resolved, and her appetite had significantly improved. Although the patient no longer required supplemental oxygen at rest, she still depended on HOT for outdoor activities due to mild respiratory distress and reduced oxygen saturation levels. While the treatment successfully mitigated the life-threatening condition, the patient’s quality of life was notably diminished compared to their status prior to osimertinib administration. At the 3-month follow-up after discharge, the patient demonstrated continued recovery. She was able to ambulate outdoors without the need for supplemental oxygen, and her functional capacity had gradually improved. Osimertinib was not re-administered.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

This case report highlights a rare and severe instance of ILD requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation during osimertinib adjuvant therapy following lung cancer resection. To date, Mitsuya et al. have reported the only other documented case of severe osimertinib-induced ILD in the adjuvant setting after resection of EGFR-mutated NSCLC (4). Although their case did not necessitate intubation, it shared key features with ours, such as the rapid onset of severe ILD and the need for steroid therapy. However, our case is particularly notable for requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation, emphasizing that severe, life-threatening ILD can develop even in patients without apparent risk factors. As the use of adjuvant osimertinib increases, similar cases may become more frequent, underscoring the need for heightened clinical awareness and monitoring.

Patients eligible for adjuvant therapy after radical resection include a certain number of potentially disease-free patients, with no cytologic remnant cells (R0) that do not require adjuvant therapy. Therefore, patient selection is important. Predicting which patient may benefit from adjuvant EGFR-TKI remains difficult, but improved identification of high-risk groups could help avoid unnecessary treatment (6). Patients with advanced stage, pleural invasion, or limited resection may experience postoperative relapse who underwent complete resection for early NSCLC with EGFR mutation (7). EGFR mutations are an independent risk factor for recurrence, strongly linked to systemic recurrence regardless of stage. Park et al. further emphasized their role in recurrence risk in completely resected NSCLC, highlighting the importance of genetic profiling in postoperative care (8).

Potential adverse events should be reaffirmed despite the relatively few adverse events of osimertinib. ILD after osimertinib treatment was observed in only 11 of 275 (4%) patients in the FLAURA trial, and none of these cases were fatal (2). However, ILD occurs as a potentially critical event, especially in Japan (3). Risk factors for EGFR-TKI-induced ILD include gender, age, smoking history, ILD history, and performance status (9). In addition, genetic factors, such as specific EGFR mutations, and the use of concurrent medications like immunosuppressants or antibiotics may also contribute to ILD risk (10). Patients with these known risk factors should be closely monitored. However, as demonstrated in the current case, severe ILD can also occur in patients without any obvious risk factors, such as those with no smoking history, no prior ILD, and no apparent comorbidities. This highlights the need for heightened vigilance, even in seemingly low-risk patients, as EGFR-TKI-induced ILD can present unpredictably. Early recognition of symptoms, along with a personalized approach to monitoring, is crucial for managing these patients.

Although high-dose corticosteroids temporarily suppressed inflammation, tapering the steroids before achieving sufficient control may have allowed residual inflammation to flare up again. This underscores the importance of carefully balancing steroid tapering with adequate disease control, especially in cases with significant inflammatory activity. In this case, treatment was initiated before ILD progressed to a diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) pattern, where steroid responsiveness is typically poor. While two courses of steroid pulse therapy were required, the treatment was ultimately effective. Delayed initiation of therapy, often resulting in fibrosis-dominant DAD patterns, has been reported to reduce corticosteroid responsiveness (11). The immediate improvement observed in this case following two courses of steroid pulse therapy suggests that early intervention at an inflammation-dominant stage can achieve favorable outcomes. Furthermore, this highlights the potential role of timely corticosteroid administration in preventing disease progression to steroid-resistant states. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are therefore crucial for managing ILD. Patient education is important for early detection of ILD symptoms that might occur while receiving osimertinib. Patients should be encouraged to contact their hospital without hesitation if any concerns arise while taking the medication. Early response saves patients with ILD.

Attempting to rechallenge osimertinib in the perioperative period after ILD development should be discouraged. A rechallenge should be considered with shared decision-making, discussing the risks of lung cancer and ILD recurrence with the patient. This is a point that greatly varies in character from the stage IV advanced lung cancer treatment and adjuvant therapy (11-13). Some reports mention the requirement to accumulate clinical data on perioperative re-administration in mild to moderate ILD cases, but the necessity of perioperative re-administration remains questionable considering the position of postoperative adjuvant therapy (4). Re-administration should be considered when lung cancer recurs.

Strengths of the study

This case report highlights several important strengths. It provides a rare, detailed account of osimertinib-induced ILD in the postoperative adjuvant setting, offering valuable insights into its clinical presentation, management, and prognosis. The case also underscores the critical importance of timely diagnosis and intervention, as well as the potential for steroid pulse therapy to achieve symptom resolution in severe cases. Additionally, it draws attention to the complexities of tapering corticosteroids and the risk of relapse, which may inform clinical decision-making in similar scenarios.

Limitations

As a single-case report, the generalizability of our findings is inherently limited. However, beyond this inherent limitation, we acknowledge several additional constraints. First, while the diagnosis of ILD was timely, earlier recognition of subtle initial symptoms might have allowed for more proactive intervention. Second, distinguishing osimertinib-induced ILD from other causes, such as infectious or inflammatory conditions, remains a diagnostic challenge. Third, although the treatment approach was ultimately successful, it raises questions about optimizing steroid tapering protocols to minimize the risk of relapse while avoiding prolonged corticosteroid exposure.

Conclusions

Severe osimertinib-induced ILD is a very unfortunate turn of events, particularly in the context of postoperative adjuvant therapy. Careful patient selection and sufficient informed consent are required when administering adjuvant osimertinib with potentially serious side effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-203/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-203/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-24-203/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1711-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:113-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohe Y, Imamura F, Nogami N, et al. Osimertinib versus standard-of-care EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment for EGFRm advanced NSCLC: FLAURA Japanese subset. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2019;49:29-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitsuya S, Arai M, Kanaoka K, et al. Severe Drug-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease After Administration of Osimertinib as Adjuvant Treatment for Resected EGFR-Mutated NSCLC: A Case Report. JTO Clin Res Rep 2024;5:100631. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf

- Jung HA, Lim J, Choi YL, et al. Clinical, Pathologic, and Molecular Prognostic Factors in Patients with Early-Stage EGFR-Mutant NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:4312-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim KY, Kim HC, Kim TJ, et al. Factors Associated with Postoperative Recurrence in Stage I to IIIA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation: Analysis of Korean National Population Data. Cancer Res Treat 2025;57:83-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park HK, Choi YD, Yun JS, et al. Genetic Alterations and Risk Factors for Recurrence in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Who Underwent Complete Surgical Resection. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:5679. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukuda Y, Uchida Y, Ando K, et al. Risk factors for interstitial lung disease in patients with non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Investig 2024;62:481-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohmori T, Yamaoka T, Ando K, et al. Molecular and Clinical Features of EGFR-TKI-Associated Lung Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:792. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kashizaki F, Chen H, Miyasaka A, et al. Safety of Readministration of EGFR-TKI After Onset of Interstitial Lung Disease in Advanced EGFR-Mutated NSCLC: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Lung Cancer 2024;25:e52-e57.e2.

- Kanaji N, Ichihara E, Tanaka T, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Re-administration of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) After EGFR-TKI-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease (CS-Lung-005). Lung 2024;202:63-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mimura C, Kaneshiro K, Fujimoto S, et al. TAPO in first-line osimertinib therapy and continuation of osimertinib. Thorac Cancer 2023;14:584-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Osako T, Takuwa T, Shindo Y. Life-threatening interstitial lung disease with adjuvant osimertinib after complete resection of non-small cell lung cancer: a case report. AME Case Rep 2025;9:56.