Guidelines to authors publishing a case report: the need for quality improvement

The decline of the case report

The place of case reports in the medical literature has and remains a much-debated topic. Among the various medical genres the case report is probably the oldest dating back to Egyptian times. A case report (from the Latin casus) can best be understood as a happening, an event or an occurrence. Some consider that the patient or the person as the case, when strictly it is the disease or the clinical event in question, is the case. A case report can be defined as “a detailed description of the experience of a single patient” or more elaborately “a formal summary of a unique patient and their illness, including the presenting signs, symptoms, diagnostic studies, management course and outcome” (1).

During the period 1946–1976, three of the “top 10” medical journals, the Journal of the American Medical Association, the Lancet, and the New England Journal of Medical, case reports and case series comprised 38% of published articles (2). The authors defined a “case report” as including 10 or fewer patients. Later during the period 1971 to 1991, there was a reduction from 30% to 4% of published case reports, in the same three journals (3). When Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) entered the scene, there was a shift with more emphasis on large numbers of quantitative studies. The randomised controlled trials achieved highest ranking with editors and the case report/series was relegated to the lower end. In addition to the prestige of publishing articles with high ranking on the evidence hierarchy, the journal achieved more citations, which culminated as the basis for calculating the impact factor (4). Case reports are, in general, cited less often than reviews, case-controlled studies, cohort studies, meta-analysis, and randomised controlled trials (5). Publishing case reports, therefore, was perceived as having the potential to lower a journal’s impact factor and standing amongst the academic medical community. Several journals subsequently either banned case reports or applied more stringent criteria (quality, novelty, exceptional interest, brevity, relevance) before accepting them for publication (6).

The resurgence/revival of the case report

In the 1990’s there was a fascination with narrative and qualitative research which had developed in some fields of medicine. Although most of the published case reports do not follow stringent criteria for qualitative research, they do have some qualitative characteristics. EBM had been met with some skepticism and critique gained support for other methods for reporting day-to-day progress in science such as case reports ability to detect novelties thereby generate new scientific hypothesis. Several editorial and time-line events and hypothesis have been proposed which occurred during the 1990’s (4).

By 1995, the Lancet introduced a section of peer-reviewed “Case Reports”, with a space limit of one page and 600 words, hoping to encourage the younger clinicians and trainees to submit (6). In 1997, the American Journal of Psychiatry, after a decade of not publishing case reports introduced the “Clinical Case Conference” as a regular feature (7). While others editors introduced alternatives modes for the publication of case reports under different guises such as “Clinical Picture”, “Hindsight”, “Perspectives”, “Commentary” or even “Letters to the Editor” much of which became incorporated into the calculation of the impact factor.

In 1998, the BMJ launched a new type of article called “The Evidence-Based Case Report” (8). This new kind of case report should not present new findings but illustrate the diagnostic and therapeutic process. At the same time the Journal of Clinical Oncology introduced the process of presenting a case showing how to negotiate good care and treatment in a cancer patient when the best evidence from EBM was at odds with the patient’s preferences (9).

Online publishing

The development of online publishing is considered to have been a major factor contributing the most to the revival of case reporting. By 2007, the first international PubMed-listed medical journal publishing only case reports were established (10,11). Since then there has been an explosion of online only, with open access journals exclusively publishing case reports and case series. Some of these are independent electronic journals while other are sister journals of established hard-copy journals, e.g., the BMJ Case Reports (launched 2008) and the International Journal of Surgery Case Reports (launched 2010), which are subscription with open access and published manuscripts are peer-reviewed. This format removes the limitation of page space. One of the major perceived advantages with the online publishing is the rapid publication. Support for the case report, focusing on patients with rare diseases was advocated by the Chief Medical Officer for England (2009) and subsequently recommended by the European Commission (2010). The reasoning being that the diagnosis is often late or not at all, and that by “advertising” the symptoms and signs of such diseases, it was perceived that there would be an improvement in clinicians’ skills (12,13). Documentation of the history as outlined above allows for an inference be reached, that the time has come for “narrative-based-medicine” and a widening scope with a new curiosity for the single individual and for a revival of qualitative research methods (4).

To date many of the case-report online journals (41%) have been indexed in PubMed, which facilitates the discovery of case reports by researchers and clinicians and increases their prospects of influencing medical research or practice. The vast majority of case report journals (94%) are open access meaning that their contents are available online for anyone to read without a subscription. The cost of running most of these journals is covered by a standard article-processing charge levied on articles that are accepted for publication or a smaller number of case report journals are subscription based, with some providing an open access option for a fee (14).

An unfortunate outcome of the open access publishing movement is the author-pays model which is a particular problem in the biomedical domain (15-17). These journals primarily exist to collect article processing charges without providing much value in return, such as solid peer review, professional editing and typesetting, preservation of journal contents, or indexing major article databases (14,18). The growth in the number of case report journals has provided authors multiple avenues form publication but, at the same time, it has introduced a new level of uncertainty in the journal selection process. Factors to consider when choosing a journal are: the topics the journal covers, the target audience, length restrictions, and the time to publication (19). Open access publications, many of which have come under criticism as predatory and choice should be made on journals that offer high visibility, relatively rapid publication, and transparent publication policies (20). A predatory journal is characterised by their behaviour: aggressive recruitment emails, unrealistic promises regarding publication, and ultimately worthless peer-review (21,22)

So, what about the case report!

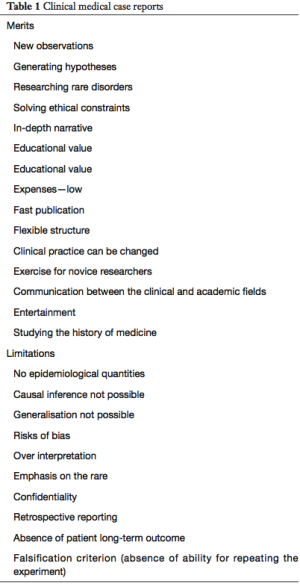

The merits and limitations of clinical case reports have been outlined and discussed (Table 1) (23). The concept of reporting having a flexible structure remains controversial and some commentators argue for a more standardised structure (24), the ultimate decision should rest with the editor. The case report maturing into a case series may generate ideas and trigger further research—a bridge between practicing clinicians and academics (25). Limitations such as not representing a population sample requires more such cases being reported, publication bias can be a problem as editors always “like a good news outcome” rather than an unfavourable outcome. Another limitation is over-interpretation or misinterpretation on the basis of a single case-report which is always a temptation, usually involving an emotive story, which should be guarded against by reviewers and more so editors. Confidentiality is a responsibility of both authors and publishers and a decision for a written informed consent from patients before publishing may be required on occasions, where identity from pictures, geographical location and occasionally rarity of disease or event (23).

Full table

Journals that welcome case reports are said to often put more emphasis on style and design than on content in their “instructions for authors’ section (26). The “CARE guidelines” (CAre REport) circulated widely in the world of medical journals in 2013, used a consensus-based methodology involving 27 participants which resulting in a 13-item checklist for reporting medical case reports. The group concluded that “implementation of the CARE guidelines by medical journals would improve the completeness and transparency of published case reports and that the systematic aggregation of information from case reports will inform clinical study design, provide early signals of effectiveness and harms, and improve healthcare delivery” (27). Reporting and research to guidelines is well established and exists for a variety of studies designs including randomised controlled trials, observational studies, and for systematic reviews and meta-analysis.

And the surgical community

The surgical community had express the usefulness of the case report (28-30) and their scientific and educational content, and felt that there remained a place for editors to consider the novelty and felt that they required their own identifiable criteria to maintain a position of importance. When a surgical journal experiences a “tsunami” of case report submissions, and in 2007 the hard-copy journal was formed by more than 25%. Having implemented a policy of non-acceptance in the late 2007, but despite instructions etc. case reports continued to be submitted, and responded by accepting on high novelty and quality. Submission continued and ultimately a sister journal was set-up exclusively for case reports. Arising out of this experience the publishers and editors agree to set out an ambitious plan to develop the science of case reports and raise their academic value (31).

Following a systematic review of the 193 journals within the Journal Citation Report 2014 (surgery category) published by Thomson Reuters was undertaken. The online guide for authors for each journal was screened by two independent groups and results were compared. Data regarding the presence and strength of recommendations to use reporting guidelines was extracted. These journals had a median impact factor of 1.526 (range, 0.047–8.327), with a median of 145 articles published per journal (range, 29–659), with 34,036 articles published in total over the 2-year period 2012–2013. The majority (62%) of surgical journals made no mention of reporting guidelines within their guidelines for authors. Only 73 (38%) mentioned guidelines, only 14% (10/73) required the use of all relevant reporting guidelines. The most frequent reporting guideline was Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) (46 journals). The CONSORT was introduced in 1996, revised in 2001 and again in 2010. It was concluded that guidelines for surgical journals needed improving and authors, reviewers and editors should work to ensure that all publications is reported against guideline standards (32).

So, the CARE statement was used as the basis for a Delphi consensus. The Delphi questionnaire was administered via Google Forms and conducted using standard Delphi methodology. A multidisciplinary group of surgeons and others (59 total) with expertise in the reporting of case reports were invited to participate. In round one, participants were asked how each of the CARE statements should be changed and what additional information were needed. Revised and additional items from round one were put forward into a further consultation rounds, voting agreement was on a 9-point Liker scale. The SCARE (Surgical CAse REport) guidelines that were ultimately agreed consisted of a 14-item checklist (33). Following the implementation of the SCARE guidelines resulted in a 10% improvement in the reporting quality of surgical case reports published in a single journal. Adherence to SCARE reporting guidelines by authors, reviewers and editors should be improved to boost reporting quality. Journals should develop their policies, submission processes and guide authors to incorporate the guidelines (34).

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Nissen T, Wynn R. The history of the case report: a selective review. JRSM Open 2014;5:2054270414523410. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. Clinical research in general medical journals: a 30-year perspective. N Engl J Med 1979;301:180-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDermott MM, Lefevre F, Feinglass J, et al. Changes in study design, gender issues, and other characteristics of clinical research published in three major medical journals from 1971 to 1991. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10:13-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nissen T, Wynn R. The recent history of the clinical case report: a narrative review. JRSM Short Rep 2012;3:87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsopoulos NA, Analatos AA, Ioannidis JP. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. JAMA 2005;293:2362-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bignall J, Horton R. Learning from stories--The Lancet's case reports. Lancet 1995;346:1246. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andreassen NC. The state of the Journal. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1-2. (Editorial). [Crossref]

- Godlee F. Applying research evidence to individual patients. Evidence based case reports will help. BMJ 1998;316:1621-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Browman GP. Essence of evidence-based medicine: A case report. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1969-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kidd M, Hibbard C. Introducing Journal of Medical Case Reports. J Med Case Rep 2007;1:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rison RA. A guide to writing case reports for the journal of Medical Case Reports and BioMed Central Research Notes. J Med Case Rep 2013;7:239. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. 2009 Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer 2010. Available online: http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/en_annual_report_2010.pdf

- Taylor CM, Karet Frankl FE. Developing a strategy for the management of rare diseases. BMJ 2012;344:e2417. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akers KG. New journals for publishing medical case reports. J Med Libr Assoc 2016;104:146-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butler D. Investigating journals: The dark side of publishing. Nature 2013;495:433-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez FR, Beall J, Forero DA. Spurious alternative impact factors: The scale of the problem from an academic perspective. Bioessays 2015;37:474-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Maduekwe O, et al. Potential predatory and legitimate biomedical journals: can you tell the difference? A cross-sectional comparison. BMC Medicine 2017;15:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferris LE, Winker MA. Ethical issues in publishing in predatory journals. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2017;27:279-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chandra R, Fisher EW, Jones TM, et al. Open Access: Is There a Predator at the Door? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;158:401-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rison RA, Shepphird JK, Kidd MR. How to choose the best journal for your case report. J Med Case Rep 2017;11:198. Erratum in: J Med Case Rep 2017;11:287. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roberts J. Predatory Journals: think before you submit. Headache 2016;56:618-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moher D, Moher E. Stop Predatory Publishers Now. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:826-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nissen T, Wynn R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:264. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aronson JK. Anecdotes as evidence. BMJ 2003;326:1346. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Descriptive studies: what they can and cannot do. Lancet 2002;359:145-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sorinola O, Olufowobi O, Coomarasamy A, et al. Instructions to authors for case reporting are limited: a review of a core journal list. BMC Med Educ 2004;4:4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE Guidelines: Consensus-based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline Development. Glob Adv Health Med 2013;2:38-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richtsmeier WJ. Case report. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:926. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scott JR. In defense of case reports. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:413-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kokudo N. How case reports have contributed to the progress of surgery. Surg Case Rep 2015;1:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agha R, Rosin RD. Time for a new approach to case reports. Int J Surg Case Rep 2010;1:1-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agha RA, Barai I, Rajmohan S, et al. Support for reporting guidelines in surgical journals needs improving: a systematic review. Int J Surg 2017;45:14-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Saeta A, et al. The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int J Surg 2016;34:180-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agha RA, Farwana R, Borrelli MR, et al. Impact of the SCARE guideline on the reporting of surgical case reports: A before and after study. Int J Surg 2017;45:144-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Bradley PJ. Guidelines to authors publishing a case report: the need for quality improvement. AME Case Rep 2018;2:10.