Intimal sarcoma of the pulmonary artery, a diagnostic enigma

Introduction

Patients with cardiac tumours present mostly non-specific symptoms which vary according to the location and the infiltration of the tumour. Besides the medical history, the diagnosis is usually based on an echocardiography, a computed tomography and a magnetic resonance imaging. According to autopsy studies, the frequency of cardiac tumours is 0.02%, 75% of which are benign and 25% are malignant. Myxomas are the most common benign tumours (50–70%) while angiosarcomas are the most common malignant neoplasms followed by rhabdomyosarcomas. Sarcomas can be further sub-classified into angiosarcomas, synovial sarcomas, intimal sarcomas, fibrosarcomas, osteosarcomas and pleomorphic sarcomas. The intimal sarcoma is a rare tumour in the area of the pulmonary artery (1). The rather distinctive characteristic of this tumour is its intraluminal growth with obstruction of the original vessel, 80% of the tumours are discovered in the area of the truncus pulmonalis while some of them also affect the pulmonary valve up to the right ventricular outflow tract. The survival time for this type of soft tissue sarcoma is very short; the median survival time without surgical resection is 1.5 months. Due to the rareness of this entity it is not completely clear whether to use surgical resection, chemotherapy or radiation therapy for treatment, or a combination thereof (2).

Case presentation

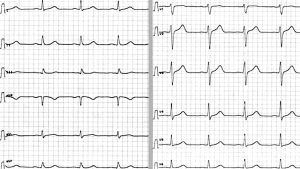

During the past months, the 61-year-old male patient had been suffering from exertional dyspnoea in response to mild exertion. He was also complaining about a chest pain during the past weeks and about a tickling cough irritation, which had declined in the meantime. There was no weight loss but the frequency of night sweats was increased. The patient worked as a craftsman exposed to glass wool and he had never smoked. The medical history included a left-sided testicular carcinoma orchiectomy, lymph node removal and adjuvant chemotherapy in 1980. Four months prior to his actual hospitalization, he had been given a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) via a chest CT. The cause of the PE was unclear at that time. Anticoagulation therapy with Rivaroxaban was needed for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc Score of 2. It’s worth mentioning that the patient had a short stay in Egypt in November 2015 and in South Africa in April 2016.The lab results, apart from a mild “eosinophilia”, have not shown any pathological results (Figures 1,2).

CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA)

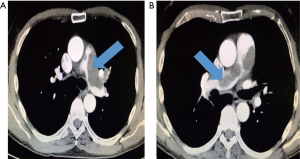

The contrast agent-enhanced chest CT scan showed a contrast defect in the main pulmonary artery with a delayed perfusion in the left lung without demonstrating any perfusion defects in the right lung. Compared with the previous findings of the chest CT, despite an effective oral anticoagulation, there was no decrease in the size of the described mass in the main branches of the pulmonary artery; as a result, the diagnosis of PE seemed unlikely (Figure 3).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Hypodense lesions in the main pulmonary artery were detected on T1w. No structures were found in the lobar segmental arteries. The contrast agent-enhanced filling defects, with consecutively reduced and delayed perfusion in the whole left lung, without perfusion disorders in the right lung, were indicative of an intravascular tumour rather than a recurring PE. Parasitic infestation was also included in the differential diagnosis. The occurrence of eosinophilia was tentatively taken into consideration, but after running extensive diagnostic tests for parasites no relevant findings were found (stool samples for Cryptosporidium parvum, Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar and Giardia lamblia-antigen were negative). In order to exclude vasculitis, a detailed medical evaluation followed without relevant findings (Figure 4).

The patient was referred to the Heart Centre of the Heidelberg University Hospital for further diagnosis by means of a biopsy and a possible surgical resection. After discussing the case, a left catheterization and right heart catheterization with biopsy were performed. The results of the coronary angiography excluded hemodynamically relevant coronary heart disease. The final histopathological examination showed an intimal sarcoma of the pulmonary artery. There were no infiltrates of a germ cell tumour (testicular tumour in 1980 orchiectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy), a carcinoma, a lymphoma or an angiosarcoma. We discussed the case thoroughly; no thoracic surgical intervention was possible. Finally, the case was discussed in the Interdisciplinary Tumour Conference of the Heidelberg University Hospital and since a surgery was not possible, palliative radiation was recommended.

Discussion

Because of the clinically common non-specific symptoms and the small number of cases regarding the primary pulmonary artery sarcoma (PAS), in many cases the correct diagnosis is delayed, because this is most commonly confused with PE or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) (3). As a result, the patients are often advised to undergo surgical intervention only when the tumour is in an advanced stage, something that obviously has a negative effect on the outcome. The differential diagnosis between an intravascular tumour of the pulmonary artery and a thrombus is challenging but it can be assisted through the imaging of the thorax and the vessels via CT, positron emission tomography (PET)-CT and MRI. Biopsy (transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy) may be considered as the final diagnostic procedure in order to receive the precise diagnosis. The differentiation between thrombus and tumour of the pulmonary artery is not possible with the use of thorax-CT. PET-CT with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) should be used in order to differentiate between PAS and PE on the basis of the intensity of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake at the level of the tumor filling defects. It is important to mention at this point, that there are cases where a clear differential diagnosis of these two entities is not feasible because of equivocal results (2,4-6). Cardiac magnetic resonance can also be used in order to provide tissue characterization of the lesions and to help differentiation between the thrombotic and neoplastic components, relying on the degree of vascularity and tissue edema (5). Cardiac magnetic resonance uses specific sequences to differentiate tumors from thrombus, relying on the delayed retention of gadolinium within the extracellular matrix of tumors (5-7). In black-blood T1-weighted sequences after administration of a paramagnetic contrast agent, cardiac masses (e.g., PAS) showed significant contrast enhancement, whereas thrombi did not enhance (2). On the other hand, the lack of echocardiographic signs of a right ventricular dysfunction (e.g., dilatation, hypokinesia or pressure stress of the right ventricle, paradoxical septal motion, increased pulmonary artery pressure, abnormal tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and eccentricity index, congestion of the inferior vena cava and the hepatic veins with lack of inspiratory collapse) plus the absence of elevated markers of myocardial damage/strain (cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides) do not support a PE. Despite all these, the above-mentioned signs may be present in the case of large-sized tumours of the pulmonary artery, causing obstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract. The absence of predisposing factors for PE (no venous thrombosis of the lower limbs on colour Doppler ultrasound, no finding suggestive of hypercoagulable state) and the progressive worsening of dyspnoea in patients with an intraluminal filling defect despite anticoagulation therapy, are factors suggestive of PAS. The lack of response to anticoagulation therapy correlated with the imaging findings may be decisive in the diagnosis. A correct early diagnosis of the PAS is of fundamental importance and the clinician is usually the first to raise a suspicion of PAS in patients with severe dyspnoea and filling defect in the pulmonary artery, unresponsive to anticoagulation therapy. The purpose of this paper is to provide recommendations for the differential diagnosis and treatment of this uncommon and underdiagnosed disease (Table S1). Regarding the differential diagnosis, apart from the diseases, we should also take into account possible respiratory motion artifacts or flow related artifacts (caused by inadequate mixing of contrast in the bloodstream) in CTPA. Due to the poor prognosis of the disease, particular awareness is needed to diagnose it at the earliest possible stage and the implementation of a standard protocol in order to establish the differential diagnosis with PE or CTEPH, with which this malignancy is most commonly confused.

Full table

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

References

- Wang H, Li Q, Xue M, et al. Cardiac Myxoma: A Rare Case Series of 3 Patients and a Literature Review. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36:2361-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attinà D, Niro F, Tchouanté P, et al. Pulmonary artery intimal sarcoma. Problems in the differential diagnosis. Radiol Med 2013;118:1259-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kostic S, Guth S, Bachmann G, et al. Sarcoma of the pulmonary artery mimicking pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burke AP, Cowan D, Virmani R. Primary sarcomas of the heart. Cancer 1992;69:387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rice DC, Reardon MJ. Left heart sarcomas. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2010;6:49-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cox JE, Chiles C, Aquino SL, et al. Pulmonary artery sarcomas: a review of clinical and radiologic features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1997;21:750-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parish JM, Rosenow EC 3rd, Swensen SJ, et al. Pulmonary artery sarcoma. Clinical features. Chest 1996;110:1480-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Barmpas A, Giannakidis D, Fyntanidou V, Koulouris C, Mantalobas S, Pavlidis E, Koimtzis G, Katsaounis A, Michalopoulos N, Alexandrou V, Aidoni Z, Tsakiridis K, Kosmidis C, Amaniti A, Zarogoulidis P, Kesisoglou I, Sapalidis K. Intimal sarcoma of the pulmonary artery, a diagnostic enigma. AME Case Rep 2019;3:32.