Multiple spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks: a rare case report and review of literature

Introduction

Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak (sCSFL) is a rare phenomenon that is gradually becoming more understood in recent years. sCSFL are most commonly found in obese, middle aged females (1). It is believed that increased intracranial pressure (ICP) may result in thinning of the skull base and eventual disruption of the dura mater. In keeping with this theory, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) has been shown to be strongly associated with the condition (2). An even more rare entity occurs when sCSFL patients present with multiple cerebrospinal fluid leaks (mCSFLs) (3). There have been some small retrospective reviews on mCSFLs published in the last 10 years. However, it was only until 2020 that a publication focused on the mCSFL patient cohort. Although this multi-centre retrospective review was relatively large with a total of 25 patients, there were limitations that ultimately illustrated the need for future prospective studies with long-term follow-up (4). We present an interesting case of a 45-year-old female with mCSFLs in the left posterior table of the frontal sinus and roof of the right ethmoid sinus and the planum of the right sphenoid sinus. In addition, we provide a current review of the literature on mCSFLs.

We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-21-36).

Case presentation

A 45-year-old female with a BMI of 52 presented with a 5-week history of a sudden onset of bilateral clear nasal discharge. It was initially misdiagnosed as allergic rhinitis and treated accordingly. With time the amount of clear rhinorrhea progressively increased. She eventually developed symptoms of meningitis with severe headaches, neck pain and photophobia. She was admitted and started on medical treatment. The nasal discharge was positive for beta-2-transferrin. The patient had no previous history of surgery or trauma.

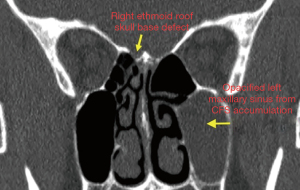

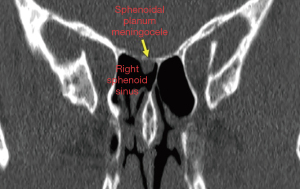

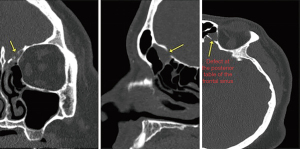

A computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed that showed multiple bony areas of skull base erosion in addition to patchy opacification of the sinuses with an air fluid level in the left maxillary sinus. The areas involved were the right ethmoid roof, right sphenoid roof, as well as the right and left posterior tables of both frontal sinuses.

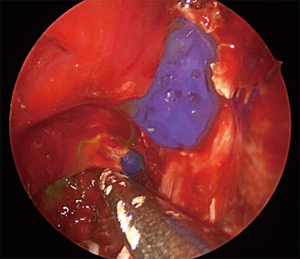

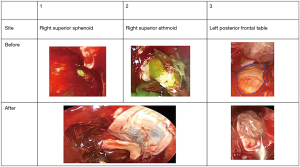

The patient underwent bilateral image guided endoscopic sinus surgery with simultaneous multilayer skull base defect repair. Surgery was conducted with CT image navigation guidance and intrathecal fluorescein [0.1 mL of 10% (10 mg) fluorescein diluted in 10 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)]. A blue light filter was also utilized. Active intra-operative CSF leakage was noted from the right posterior ethmoid roof (Figure 1) and the planum of the right sphenoid (Figure 2) sinus as well as the left posterior table of the frontal sinus (Figure 3). An encephalocele was identified at all sites. Bipolar diathermy was used to cauterize each encephalocele, overlying mucosa was stripped off surrounding the skull base defect site to fully expose the area. An underlay PDS plate was placed in the right skull base defects whereas a bone piece was placed in the smaller left posterior table defect as an initial underlay layer (Figures 4,5). Overlay free mucosa graft obtained from the floor of the nose was used as an overlay graft followed by gelfoam and tisseal used for further support.

Post-operatively a lumbar drain was left in place for 24 h and then removed. She experienced severe headaches for 3 days, a CT head ruled out any intracranial complications of bleeding or compression. The headaches eventually settled. At five weeks post-operatively, she was re-admitted with a suspicion of meningitis. She received intravenous (IV) antibiotics and recovered fully. At 3 months post-operatively the patient is doing well with no evidence of CSF leak. She has been referred to bariatric surgery. Acetazolamide was discontinued due to significant side effects. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Our patient presented with a typical history of CSF rhinorrhea, however detailed assessment of imaging and the use of intrathecal Fluorescin revealed not only one site of CSF but multiple and bilateral skull base defects that required repair. The multiple skull base defects this patient presented with required meticulous repair, the need of advanced endoscopic sinus surgery skills and additional operative time. This diagnosis should be always on the mind of skull base surgeons especially for patients who fit the profile of sCSF and complain of bilateral CSF rhinorrhea, failure to identify other sites of leakage might lead to persistent CSF leakage and hence the possibility of having complications and the need for further surgeries to repair the missed skull base defects. Furthermore, early anticipation of such cases will help in surgical planning and improved post-operative care such as the need of lumbar drain and ICP lowering medication.

A search of all studies published through January 9, 2021, reporting mCSFL cases was conducted using PubMed. Studies were identified independently by 2 authors (JAP and LAS) using a keyword search strategy. The initial search was performed using the single term “multiple spontaneous CSF leak” with all available abstracts reviewed. In addition, reference lists of all studies identified were scanned for studies not evident in the primary literature search, including sCFL reports that may have included mCSFL cases.

The literature on mCSFL has been present for decades, but further elucidation of the condition has been limited by its apparent rarity. There have been multiple case reports on the matter, with the first known case being reported in 1986 (5). Following this, 10 studies focusing on mCSFLs have been described, including a more recent retrospective multi-centre account of 25 patients (4) (Table 1). The Dallan study is the largest to date to focus on mCSFLs and provides tremendous insight into the condition (4). They successfully emphasized the existence of mCSFLs, association with IIH, and possible new links to demographics.

Table 1

| Study (author, year) | Study design | # mCSFL patients | Demographics (age, gender ratio, BMI) | Follow-up (likely median or average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferguson, 1986 (5) | Case Series/Retrospective Review | 1 | Avg age: 48 F:M ratio: 14:18 BMI: N/A |

N/A |

| Pappas, 1996 (6) | Case Report (n=2) | 1 | Avg age: 59.5 F:M ratio: 1:1 BMI: N/A |

Up to 4 years |

| Raghavan, 2002 (7) | Case Report | 1 | Age: 72 Female BMI: N/A |

5 months |

| Lopatin, 2003 (8) | Retrospective Review (sCSFL) | 1 | Age: 15–64 yrs F:M ratio: 15:6 BMI: >30 n=5 |

Range: 9 to 42 months |

| Schlosser, 2003 (9) | Retrospective Review (CSF Leaks) | 5 | Avg age: 49.6 years F:M ratio: 13:3 Avg BMI: 35.9 kg/m2 (F only) |

Avg: 14.1 months |

| Gonzàlez-Garcia, 2006 (10) | Case Report | 1 | Age: 62 Female BMI: N/A |

2 years and 5 months |

| Woodworth, 2008 (11) | Retrospective (sCSFL) | 9 | Avg age: 61 F:M ratio: 43:13 Avg BMI: 36.2 kg/m2 |

Avg: 34 months |

| Chaaban, 2012 (12) | Prospective (sCSFL) | 12 | Avg age: 51.2 F:M ratio: 32:14 Avg BMI: 35.6 kg/m2 |

Avg: 22 months |

| Zanoletti, 2013 (13) | Case Report | 1 | Age: 49 Female BMI: >30 |

1 year |

| Lieberman, 2015 (3) | Retrospective | 8 | Avg age: 50.9 F:M ratio: 35:9 Avg BMI: 34.5 kg/m2 |

Avg: 9.2 months |

| Dallan, 2020 (4) | Retrospective | 25 | Avg age: 55.3 F:M ratio: 11:14 Avg BMI: 29.7 kg/m2 |

Avg: 32.8 months |

#: Number. mCSFL, multiple cerebrospinal fluid leaks; BMI, body mass index; N/A, not applicable; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

However, Dallan and colleagues pointed out a handful of notable limitations to their work. In their study, they had little data on sleep apnea, which may play an important role in IIH development (4). In addition, their study population represented patients that were similar radiographically to typical IIH patients but behaved very differently clinically. Their “possible” control group patients varied greatly compared to their mCSFL counterparts with a male to female ratio of 1:5 and 3:2, respectively. It was postulated that these differences could be attributed to variations in IIH being linked demographically, as this was a multicentre study involving four different countries. To this point, they made a comparison of IIH being akin to blood hypertension as an umbrella term for various different subtypes of the condition, implying that the differences in geographical data possibly led to the atypical representation of mCSFL patients in their retrospective study.

This has implications for any future studies in the area of mCSFLs and demonstrates a need for prospective studies that take into consideration demographic and geographical information for both more accurate interpretation and better recruitment. Focusing on a study population with a high prevalence of IIH, with subsequently a percentage likely representing mCSFLs, makes for higher recruitment numbers in studies for this seemingly rare entity. The prevalence of mCSFLs are less rare than once believed, with one study finding that 18.2% of their sCSFL patients had mCSFLs (3). Another group found that 5 of 16 patients (31.2%) that they operated on with presumed sCSFL rhinorrhea was indeed mCSFL (9). Therefore, with the combination of targeted demographics and seemingly underreported mCSFL cases, the feasibility of acquiring enough mCSFL patients for a small prospective study may very well be attainable.

With most of IIH patients being obese, it may be worthwhile to pursue this in an area with higher rates of morbid obesity, and thus IIH with associated mCSFLs. One study in the United States (US) found that the incidence of IIH was around twenty-fold higher in females that were 20% or more over ideal weight and aged 20 to 44 years compared to the general population (14). Countries severely affected by the obesity epidemic, such as the US, may be the most suitable demographic to commence such studies. It must be considered though, that the current understanding of these entities may be limited as extrapolated by atypical demographic representations seen in the literature for sCSFLs. One study found that their observed cases of sCSFLs did not fit into the typical age groups irrespective of the gender, despite these demographics being widely known and verified (15).

Other areas of important consideration for future studies should include putting emphasis on longer follow-up time and adequate long-term monitoring due to the underlying chronicity of increased ICP. Dallan et al. found that of 25 patients with mCSFL, 21 (84%) had two simultaneous defects, 3 (12%) had three simultaneous defects, and 1 (4%) had four simultaneous defects (4). In another study, one patient with an initial endoscopic repair of the right sphenoid for ongoing sCSFL not only required a second repair at that site 1 year later, but also was found to have tegmen tympani defects 3 years later on the same side requiring mastoidectomy (16) (Table 2). Moreover, it is likely that the chronicity of increased ICP can lead to conversion of sCSFL to mCSFL, whether that be through formation of new osteo-dural defects or new onset leaking at previous defects. IIH being chronically undermanaged could be another underlying reason for taking further prudence in ensuring proper long-term follow-up. This is further corroborated by the 5-year prospective sCSFL study by Chaaban et al., with 46% patients having recurrences (n=21) (12).

Table 2

| Study (author, year) | mCSFL locations |

|---|---|

| Ferguson, 1986 (5) | #1—R tegmen, L tegmen tympani |

| Pappas, 1996 (6) | #2—L sinodural angle sphenoid, R tegmen tympani |

| #3—R tegmen tympani, sphenoid sinus | |

| Raghavan, 2002 (7) | #4—R cribriform plate, L tegmen tympani |

| Lopatin, 2003 (8) | #5—2 x fistula in same posterior sphenoid sinus (side not indicated) |

| Schlosser, 2003 (9) | #6 to #10—No information on locations provided. |

| Gonzàlez-Garcia, 2006 (10) | #11—R cribriform plate, R tegmen antrum |

| Woodworth, 2008 (11) | #12 to #20—No information on locations provided |

| Chaaban, 2012 (12) | #21 to #32—No information on location provided |

| Zanoletti, 2013 (13) | #33—Ethmoidal roof, R antrum to epitympanum |

| Lieberman, 2015 (3) | #34—Bilateral cribriform |

| #35—L cribriform, Tegmen tympani | |

| #36—2 x defects in R cribriform | |

| #37—Bilateral cribriform | |

| #38—2 x defects in L cribriform | |

| #39—R posterior table of frontal sinus, L lateral sphenoid recess, R fovea ethmoidalis 2 years later | |

| #40—R frontal sinus, L sphenoid sinus | |

| #41—2 x defects in L lateral sphenoid recess | |

| Dallan, 2020 (4) | #42—L frontal recess, R posterior table frontal sinus |

| #43—R olfactory fissure, R mastoid | |

| #44—Bilateral tegmen | |

| #45—Bilateral tegmen | |

| #46—Bilateral tegmen | |

| #47—R sphenoid, R cribriform plate | |

| #48—L first ethmoidal foveola, R cribriform plate | |

| #49—L first foveola, L posterior table frontal sinus | |

| #50—R olfactory fissure, R tegmen | |

| #51—L frontal recess, R posterior table frontal sinus | |

| #52—R posterior table frontal sinus, R olfactory cleft | |

| #53—R anterior olfactory cleft, R posterior olfactory cleft | |

| #54—L anterior olfactory cleft, L posterior olfactory cleft | |

| #55—R sphenoid sinus lateral recess, R Internal auditory canal | |

| #56—R posterior sphenoidal wall, R posterior sphenoidal wall | |

| #57—R olfactory cleft, R tegmen | |

| #58—L clivus, R clivus | |

| #59—R posterior table frontal sinus, R posterior table frontal sinus | |

| #60—R olfactory fissure, R tegmen | |

| #61—L frontal recess, R posterior wall frontal sinus | |

| #62—L tegmen tympani, L mastoid | |

| #63—L sphenoid sinus lateral recess, L sphenoid superior wall, L olfactory cleft | |

| #64—R sphenoid sinus lateral recess, R cribriform plate, L posterior table frontal sinus | |

| #65—R anterior ethmoid, bilateral mastoid | |

| All studies | 65 cases total of documented mCSFL in literature |

mCSFL, multiple cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

To complicate matters further, mCSFLs are sporadic in nature, thus accuracy in obtaining reliable metrics for long term data may pose challenges in management of the condition. The “on-off” presentations of leaks can lead to difficulty in capturing mCSFLs at any given time. Many studies have demonstrated either incidental diagnosis of concurrent leak sites in a seemingly sCSFL patient or additional osteo-dural defects that were not actively leaking (3). Chaaban et al. identified in 21 patients via pre-operative CT that there were multiple skull base defects, but only 12 of these patients were confirmed to have active leaks that were subsequently repaired (12). Dallan et al. similarly opted for repair of encephaloceles if actively leaking (4). In contrast, Lieberman et al. opted to repair all identified skull base defects, regardless if actively leaking or not (3). It remains unclear whether or not a non-active leak site should be repaired or left alone. With that being said, careful consideration needs to be placed into the methodology for analyzing this patient population in an accurate and meaningful way, as it also may influence standard of care for managing the condition.

As a further subset of the already rare entities IIH and sCSFLs, mCSFLs have been documented in the literature for some time now. It appears that the sporadic and asymptomatic nature of the condition may represent underreported numbers. Furthermore, mCSFL may be more common than once believed and future prospective studies can be realistically achieved through targeted recruitment in the obese, middle aged, and female demographic. These studies also need long term follow-up, inclusion of additional pertinent data such as relation to OSA and IIH, as well as accurate and reliable measures that can navigate the sporadic and asymptomatic presence of mCSFLs, ultimately influencing understanding and management of the condition.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-21-36

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-21-36

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acr-21-36). ARJ: Advisory Board: Sanofi Genzyme, GSK; Consultant: SaNOtize Research and Development. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This case report has been determined to be exempt from REB review by Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Stevens SM, Rizk HG, Golnik K, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Contemporary review and implications for the otolaryngologist: Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Laryngoscope 2018;128:248-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah N, Deopujari CE, Chhapola Shukla S. Spontaneous Recurrent CSF Rhinorrhoea: A Rare Case and Review of Literature. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;69:420-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lieberman SM, Chen S, Jethanamest D, et al. Spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: prevalence of multiple simultaneous skull base defects. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2015;29:77-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dallan I, Cambi C, Emanuelli E, et al. Multiple spontaneous skull base cerebrospinal fluid leaks: some insights from an international retrospective collaborative study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020;277:3357-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson BJ, Wilkins RH, Hudson W, et al. Spontaneous CSF otorrhea from tegmen and posterior fossa defects. Laryngoscope 1986;96:635. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pappas DG Jr, Pappas DG Sr, Hoffman RA, et al. Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks Originating from Multiple Skull Base Defects. Skull Base Surg 1996;6:227-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raghavan U, Majumdar S, Jones NS. Spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea from separate defects of the anterior and middle cranial fossa. J Laryngol Otol 2002;116:546-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lopatin AS, Kapitanov DN, Potapov AA. Endonasal endoscopic repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:859-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schlosser RJ, Bolger WE. Significance of empty sella in cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;128:32-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- González-Garcia JA, Garcia-Berrocal JR, Trinidad A, et al. Endonasal Endoscopic Management of a Large Meningocephalocele in a Patient with Concomitant Middle Skull Base Defect. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2006;49:309-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woodworth BA, Prince A, Chiu AG, et al. Spontaneous CSF leaks: A paradigm for definitive repair and management of intracranial hypertension. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;138:715-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaaban MR, Illing E, Riley KO, et al. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak repair: A five-year prospective evaluation. Laryngoscope 2014;124:70-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zanoletti E, Faccioli C, Emanuelli E, et al. Spontaneous CSF Leaks Caused by Double Skull Base Defects: Case Report. J Int Adv Otol 2013;9:437.

- Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The Incidence of Pseudotumor Cerebri: Population Studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol 1988;45:875-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of Spontaneous CSF Rhinorrhea: An Institutional Experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2019;80:493-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmitt B, Badet J, Chobaut J, et al. Double Skull Base Defects with Primary Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks in a Single Patient: Temporal and Sphenoid Bones. Skull Base 2010;20:455-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Piemontesi JA, Samson LA, Alqunaee MD, Javer AR. Multiple spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks: a rare case report and review of literature. AME Case Rep 2022;6:5.