Isolated anomalous right coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ARCAPA): incidental finding in the patient presenting with angina—a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• We present a rare case of isolated anomalous right coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ARCAPA) in a man with symptoms of angina without significant coronary disease.

What is known and what is new?

• ARCAPA is a rare congenital abnormality that is associated with possible long-term complications including myocardial ischemia and left ventricular dysfunction.

• We present this case to raise awareness of the existence of these congenital coronary artery abnormalities, and to consider them as a possibility when a proceduralist encounters difficulty engaging or visualizing a coronary artery and need for possible surgical intervention to prevent associated long-term complications.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• All patients with ARCAPA should have evaluation by cardiothoracic surgery for possible surgical repair, even if asymptomatic to re-establish dual coronary system and prevent further long-term complications including heart failure and even sudden cardiac death.

Introduction

In 1945, Soloff described four possible anomalies of the coronary artery originating from the pulmonary artery, anomalous right coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ARCAPA) is one of them (1). ARCAPA is a congenital defect that was first reported in 1885 found during cadaver research by Brooks in Dublin, Ireland. Since this discovery, only about 223 cases have been reported (2). It is reported to affect approximately 0.002% of the population (3). Only 25–30% of ARCAPA cases are associated with structural heart defects (1).

ARCAPA has been diagnosed in adults and children both with a spectrum of symptoms ranging from an asymptomatic murmur to sudden cardiac death (2,4). Bimodal distribution of age is observed in symptomatic patients, with peak near birth and between ages 40 and 60 years (2). In contrast to the anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ALCAPA), it rarely leads to sudden cardiac death. Surgical correction should be considered for all patients, even if asymptomatic, and of very low risk (5). We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-23-190/rc).

Case presentation

The patient was a 52-year-old African American man with a past medical history of tobacco use disorder and obesity, presented to the emergency room for intermittent chest pain for the last 6 months. No significant family history of cardiac disease was present. The patient smoked 1–2 cigarettes daily. Vitals on admission showed blood pressure: 121/73 mmHg, heart rate: 74 b/min regular rate and rhythm, afebrile, respiratory rate: 18 breaths/min. On examination the patient was alert and oriented not in apparent distress, S1 and S2 audible, no cardiac murmur audibles. Rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable. Initial electrocardiogram (EKG) on admission showed nonspecific ST changes and no acute ischemic changes (Figure 1). The lab work showed no significant findings with troponin level of <0.03 ng/mL. The patient was evaluated by cardiology, had dobutamine stress echocardiogram (ECHO) for ischemic evaluation.

During the recovery phase of dobutamine stress ECHO, the patient reported having 10/10 chest pain with a drop in blood pressure to 90 mmHg systolic. He was subsequently given sublingual nitroglycerin and fluids. Pain did resolve and blood pressure improved after treatment. No wall motion abnormalities were noted on ECHO, but there were inferior ST depressions on EKG during the stress portion of the test. The patient had repeated blood work after the stress test which showed an elevated troponin level of 0.08 ng/mL. The patient was taken to the catheterization lab for diagnostic coronary angiogram.

Access was obtained from the right radial artery for coronary angiogram. The left coronary system was engaged with a 6 Fr extra back up (EBU) 3.5 guide catheter and selective angiogram was performed. Initial images revealed large caliber vessels and the left coronary system provided large collaterals to the right system. Multiple images were obtained from standard views with longer fluoroscopy time which revealed that the right coronary artery (RCA) was completely filling in a retrograde pattern from the left coronary system. The origin of the RCA ostium was found to arise from the pulmonary artery based on retrograde angiogram filling. No significant coronary artery disease was visualized.

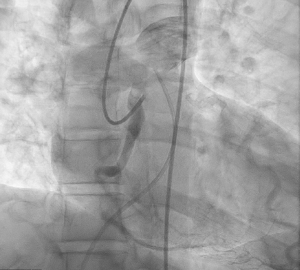

Therefore, venous access was obtained, and pulmonary artery catheter was advanced into pulmonary artery. Pulmonary artery angiogram was performed showing no clear origin of the RCA ostium. Therefore, a repeat injection of the left coronary system was performed with pulmonary artery catheter in place to visualize location of RCA origin. After multiple injections in this manner, the RCA filled in retrograde manner and drained immediately adjacent to the pulmonary artery catheter (Figure 2). There was successful visualization of the contrast dye filling the pulmonary artery trunk and bifurcating into left and right pulmonary arteries (Figure 3). No intervention was performed as no significant lesions were found. The patient started on medical therapy inpatient including aspirin 81 mg once a day, moderate dose atorvastatin and metoprolol succinate 50 mg once a day.

Patient perspective

The patient after knowing that he did not have any acute myocardial infarction or acute life-threatening condition, he did not want to pursue surgery at that point and he did not want any further intervention. The patient was subsequently discharged home on medical therapy with instructions to follow up with cardiology in an outpatient setting to be referred for surgical repair.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

We present this case to raise awareness of the existence of these congenital coronary artery abnormalities, and to consider them as a possibility when a proceduralist encounters difficulty engaging or visualizing a coronary artery and need for possible surgical intervention to prevent associated long-term complications, unfortunately in our case the patient did not want any further intervention or follow up.

ARCAPA is one of four known anomalies of the coronary arteries originating from the pulmonary artery. ALCAPA, an accessory coronary artery from the pulmonary artery and both coronary arteries from the pulmonary artery. ARCAPA is a rare anomaly as compared to ALCAPA (0.002% as compared to 0.008%) (5). ARCAPA can be isolated (78%) or associated with other cardiac congenital abnormalities (22%). The congenital abnormalities that have been associated with ARCAPA include aortopulmonary window, tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defect (VSD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and aortic stenosis (1). The patients with these associated structural abnormalities will usually be diagnosed in infancy or childhood as they are likely to have further evaluation for unexplained cardiac murmurs, heart failure or other associated symptoms. In this case, the patient was noted to have an isolated ARCAPA with no structural defects on ECHO, likely explaining such a late diagnosis.

Patients with isolated ARCAPA are generally initially asymptomatic, once symptomatic, clinical presentations can vary from angina, dyspnea, fatigue, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction and even cardiac arrest (1,2). EKG findings may be normal, or may show left ventricular hypertrophy or deep Q waves in the inferior leads (6). Different diagnostic modalities that can be utilized to diagnose ARCAPA include computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the coronaries, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and coronary angiography (1,2)

Given this patient’s clinical presentation, one would assume that a significant coronary lesion was likely, but given the angiographic findings, one must consider the possibility of microvascular disease causing troponemia, ST changes and anginal symptoms. It is possible that the low perfusion pressure and lack of adequately oxygenated blood being received by the proximal to mid portions of the RCA may contribute to these symptoms and stress test findings.

Patients with ARCAPA should be referred for surgical repair, even if asymptomatic. Based on the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease, it is a class I recommendation to surgically repair ARCAPA in symptomatic patients, and class IIa recommendation to surgically repair asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction or with myocardial ischemia attributed to the anomaly (7). The goal of surgical correction is to provide dual coronary circulation from the aorta and eliminate the left to right shunt present in most ARCAPA cases. The coronary steal phenomenon that we observe in our case report could hypothetically worsen with advancing age, atherosclerosis or microvascular disease, and should be proactively prevented with surgical correction. Catastrophic outcome can occur if the patient develops a severe lesion in the proximal left coronary system, impeding direct flow to both sides of the myocardium. The three main reported surgical techniques are surgical ligation of the RCA, surgical ligation of RCA with saphenous vein bypass grafting and re-implantation of the RCA into the aorta (8). The translocation of RCA into the aorta is the preferred surgical method, if anatomy is amenable to such. Otherwise, the other two methods mentioned above can be used.

In conclusion, ARCAPA is a rare congenital abnormality that is associated with possible long-term complications including myocardial ischemia and left ventricular dysfunction. This abnormality may present in adulthood with typical cardiac symptoms. The diagnosis of ARCAPA is best obtained via imaging modalities such as CTA coronary, cardiac MRI and/or coronary angiography. All patients should have evaluation by cardiothoracic surgery for possible surgical repair, even if asymptomatic.

Conclusions

ARCAPA is a rare congenital abnormality that is associated with possible long-term complications. The purpose of presenting this case is to increase awareness among physicians to be able to recognize possible anomalous coronary artery origins during cardiac catheterization and to understand the risk of long-term complications of ARCAPA and possible need for surgical intervention including symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-23-190/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-23-190/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://acr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/acr-23-190/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gupta R, Marwah A, Shrivastva S. Anomalous origin of right coronary artery from pulmonary artery. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2012;5:95-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guenther TM, Sherazee EA, Wisneski AD, et al. Anomalous Origin of the Right Coronary Artery From the Pulmonary Artery: A Systematic Review. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;110:1063-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1990;21:28-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Modi H, Ariyachaipanich A, Dia M. Anomalous origin of right coronary artery from pulmonary artery and severe mitral regurgitation due to myxomatous mitral valve disease: a case report and literature review. J Invasive Cardiol 2010;22:E49-55. [PubMed]

- Kim KS, Jo EY, Yu JH, et al. Anomalous right coronary artery from pulmonary artery discovered incidentally in an asymptomatic young infant. Korean J Pediatr 2016;59:S80-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balakrishna P, Illovsky M, Al-Saghir YM, et al. Anomalous Origin of Right Coronary Artery Originating from the Pulmonary Trunk (ARCAPA): an Incidental Finding in a Patient Presenting with Chest Pain. Cureus 2017;9:e1172. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1494-563. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2361. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Dairy A, Rezaei Y, Pouraliakbar H, et al. Surgical Repair for Anomalous Origin of the Right Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery. Korean Circ J 2017;47:144-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Jamal F, Waqas S, Skovira V, Sayed L. Isolated anomalous right coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ARCAPA): incidental finding in the patient presenting with angina—a case report. AME Case Rep 2024;8:75.